The Once and Future Kings of the Sea: The Saga of the Seawise Giant and the Titans That Rule the Waves Today

In the annals of maritime history, some ships are remembered for their speed, others for their luxury, and a tragic few for their demise.ription.

7/21/202513 min read

Part I: The Leviathan - A Biography of the Seawise Giant

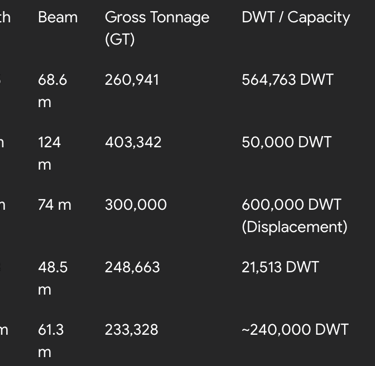

In the annals of maritime history, some ships are remembered for their speed, others for their luxury, and a tragic few for their demise. But one vessel holds a unique and uncontested title, a distinction of pure, unadulterated scale: the Seawise Giant. For three decades, it was the longest self-propelled object ever to move across the face of the Earth, a man-made island of steel whose life was as dramatic and turbulent as its dimensions were staggering. This is the story of that ship—a tale of flawed genius, audacious ambition, trial by fire, and a long, slow fade into legend. It is the story of the last true king of a bygone era, and of the new and different titans that have risen to claim its throne.

The Unwanted Giant

The story of the world’s largest ship begins not with a triumphant launch, but with a rejection. In 1974, at the height of the oil boom, a Greek shipping magnate placed an order with Sumitomo Heavy Industries, Ltd. (S.H.I.) at their Oppama shipyard in Yokosuka, Japan, for what was intended to be an Ultra Large Crude Carrier (ULCC) of unprecedented size.As construction progressed, the vessel was known only by its hull number: 1016. It was a project pushing the very boundaries of naval architecture, and those boundaries soon pushed back.

During its initial sea trials, a critical and alarming flaw emerged. When attempting to move astern, hull 1016 was plagued by severe and uncontrollable vibrations. For a vessel of this magnitude, where precise, slow-speed maneuverability is paramount for docking and safety, such a defect was not a minor inconvenience; it was a fundamental failure of design. The issue was so significant that the Greek owner, whose exact reasons remain clouded by conflicting reports of bankruptcy or a simple change of mind, refused to take delivery of the ship.

This refusal was more than a mere contractual dispute; it was a profound symptom of an engineering endeavor that had perhaps flown too close to the sun. The creation of hull 1016 was an act of exploration into the unknown physics of super-massive structures on water. The vibration problem was the unforeseen consequence of that exploration, a clear sign that theoretical designs had collided with the harsh, unpredictable realities of the physical world. The ship was an experiment, and the initial results were a failure.Following a lengthy and complex arbitration process, the shipyard was left in possession of a flawed, unnamed, and unwanted behemoth. S.H.I. eventually took formal ownership and gave the vessel its first, rather unremarkable name:Oppama. For a time, it seemed the world’s largest ship might be destined for a life of ignominy, laid up in the yard, a monument to ambition that had outstripped ability.

The Vision of a Titan

The fate of the Oppama was transformed by the vision of one man: the Hong Kong shipping magnate Tung Chao-yung, founder of the Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL). Where others saw a flawed asset, C.Y. Tung saw an unparalleled opportunity. He purchased the vessel not just to use it, but to make it even bigger.

In an audacious feat of engineering known as "jumboisation," the ship's hull was surgically cut in two. A massive, prefabricated mid-body section was then expertly spliced into the gap, lengthening the vessel by several meters and adding a staggering 146,152 tonnes of cargo capacity. When the ship was relaunched two years later, in 1981, it was rechristened with a name that was both a statement of its scale and a clever nod to its new owner:Seawise Giant, a pun on C.Y. Tung's initials.

The decision to jumboise what was already one of the largest hulls ever constructed reveals a mindset that transcended pure economic calculation. A standard business approach would have been to correct the vibration flaw and put the ship into service as quickly as possible to begin generating revenue. Instead, Tung invested immense additional time and capital into a complex and risky procedure. This suggests that the Seawise Giant was conceived as more than just a commercial tool; it was to be a flagship, a floating monument to the power and ambition of his company and of Hong Kong's burgeoning status as a global maritime hub.

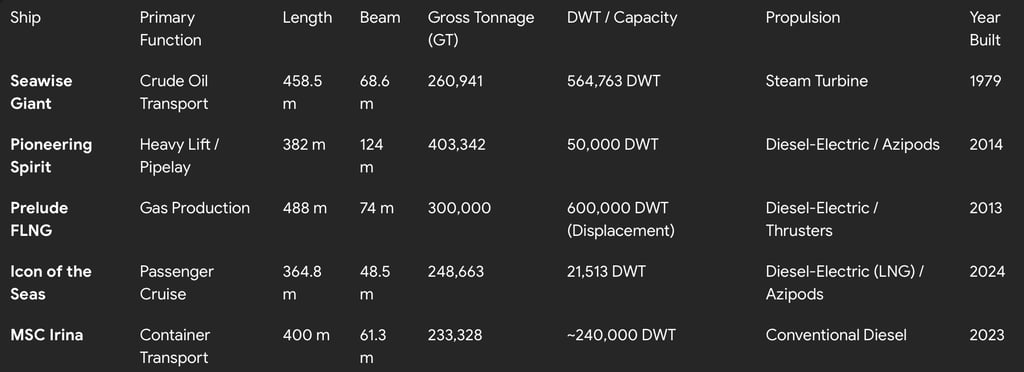

The final specifications of the reborn vessel were, and remain, mind-boggling. It was now a self-propelledobject of truly historic proportions.

A Reign of Oil and Water

With its transformation complete, the Seawise Giant began its working life, a colossal tool in the service of the global oil trade. Its primary function was to ferry enormous quantities of crude oil on long-haul voyages, typically between the oil fields of the Middle East and the refineries of the United States. But operating a vessel of such extreme dimensions was a constant exercise in navigating constraints.

Its very existence created a paradox of efficiency. On one hand, it embodied the principle of economies of scale like no other vessel before or since. By moving over 4 million barrels of oil in a single trip, it dramatically reduced the cost per barrel transported, a key advantage in the competitive world of global energy markets. On the other hand, its physical limitations imposed significant inefficiencies. The 24.6-meter draft meant that the world’s most vital maritime shortcuts were closed to it. Every voyage that might have passed through the Suez or Panama Canals had to be rerouted on much longer, more time-consuming, and more fuel-intensive journeys around the great capes of Africa's Cape of Good Hope or South America's Cape Horn.

Furthermore, its sheer bulk meant it could not simply pull into any port. Many terminals were not deep enough or large enough to accommodate it, necessitating risky and complex ship-to-ship transfers of cargo in the open ocean. The ship’s handling characteristics were equally daunting. As Captain S. K. Mohan noted during his time at the helm for the BBC series Jeremy Clarkson's Extreme Machines, bringing the vessel to a halt from its 16.5-knot cruising speed was a decision that had to be made nearly ten kilometers in advance. A simple turn required a diameter of open water measuring three kilometers. The ship did not sail through the ocean; it imposed its will upon it, demanding that the world bend to its scale.

This constant balancing act defined its operational life. The ship's profitability was perpetually tethered to a global oil market where the immense savings derived from its capacity could outweigh the equally immense costs imposed by its inflexibility. It was not an all-purpose tool but a highly specialized instrument, perfectly tuned for a very specific set of economic conditions.

Remarkably, this floating behemoth was managed by a crew of just 40 people. This small number, aboard the largest moving object on the planet, was a testament to the increasing automation and design efficiency of late 20th-century shipbuilding, a harbinger of the even smaller crew-to-size ratios that would become common on the mega-ships of the future.

Trial by Fire and the Phoenix Arc

For seven years, the Seawise Giant plied its trade, a titan of the seas but largely unknown to the public. That changed dramatically on May 14, 1988, when the ship sailed directly into the crosshairs of geopolitics. The ongoing Iran-Iraq War had spilled into the Persian Gulf, with both sides targeting the oil shipping that was the economic lifeblood of the other in what became known as the "Tanker War."

While anchored in the shallow waters off Iran's Larak Island, serving as a floating storage platform for Iranian crude oil, the Seawise Giant became a target for Saddam Hussein's Iraqi Air Force. Iraqi jets swept in and struck the stationary vessel with a volley of Exocet missiles and parachute-retarded bombs. The combination of high explosives and millions of barrels of crude oil was catastrophic. The ship was immediately engulfed in a raging inferno, the fire feeding on the very cargo it was built to carry. It burned for days before finally succumbing, sinking into the shallow sea.

The world's largest ship had become the world's largest shipwreck. It was declared a constructive total loss by its owners, seemingly a final, fiery end to its remarkable story. For almost any other vessel, this would have been the final chapter. But theSeawise Giant was not just any vessel.

Its very scale, which had defined its life, would now define its afterlife. After the war ended, a Norwegian consortium named Norman International assessed the wreck and made a stunning calculation. They determined that the cost of purchasing the sunken hull, executing one of the most ambitious salvage operations in history, towing it thousands of miles to a shipyard, and conducting massive repairs was still less than the potential value of the resurrected vessel. This was a testament to the concept of being, in a very real sense, too big to fail. The potential future earnings from its unparalleled cargo capacity justified a resurrection that would have been economically unthinkable for a lesser ship.

In a monumental effort, the wreck was refloated and towed to the Keppel Corporation shipyard in Singapore. The repairs were epic in scale, requiring 3,700 tons of new steel to patch the wounds of war. In October 1991, nearly three and a half years after its sinking, the ship was reborn. It sailed out of the shipyard under a new, optimistic name:Happy Giant. The titan had risen from its watery grave.

The Long Twilight and a Titan's Rest

The resurrected Happy Giant did not wait long for its next chapter. In 1991, it was purchased for $39 million by the Norwegian shipping magnate Jørgen Jahre and given the name that would define its longest period of service: Jahre Viking. For the next 13 years, it sailed the world's oceans under the Norwegian flag, once again hauling crude oil and cementing its legendary status.

By the early 2000s, however, the world was changing. New environmental regulations, particularly concerning single-hulled tankers, were making vessels of its vintage a liability. The economics of operating such a fuel-hungry, aging giant were becoming increasingly challenging. Its dynamic life as a globe-trotting tanker was coming to an end.

Yet, its story was not over. In 2004, it was sold to First Olsen Tankers, which recognized that even if the ship could no longer roam, its most fundamental feature—its immense storage capacity—still had value. The vessel underwent its final transformation, being converted into a non-propelled Floating Storage and Offloading (FSO) unit. Renamed Knock Nevis, it was permanently moored in Qatar's Al Shaheen Oil Field, serving as a static offshore platform where smaller tankers could load and offload their cargo. The once-mighty voyager had become a stationary piece of industrial infrastructure.

This final role perfectly encapsulates the lifecycle of such massive assets. When a great machine becomes too old or inefficient for its primary, dynamic purpose, its life can often be extended by adapting it to a secondary, static one. But even this phase has a finite end. After five years as an FSO, the cost of maintaining the aging behemoth finally outweighed its utility. The value of the ship was no longer in what it could do, or even what it could hold, but in what it was made of.

In December 2009, the vessel was sold one last time, to Indian ship breakers. It was given its final name, Mont, and reflagged to Sierra Leone for its last journey. It sailed under its own power to Alang, in Gujarat, India—the largest ship-breaking yard on Earth. There, it was intentionally beached, its colossal bow driven into the sand, awaiting its final deconstruction.The task of dismantling the Mont was as epic as its construction. It took an estimated 18,000 laborers a full year to cut the giant apart, piece by piece, recycling its steel for new uses. But one piece was saved from the cutting torches. The ship's 36-ton anchor, the very object that held the titan fast to the seabed, was preserved. It was donated to the Hong Kong Maritime Museum, a final, tangible monument to a ship that was not just a vessel, but a statement of ambition written in steel.

Part II: The New Titans - Redefining "Largest" in the 21st Century

The scrapping of the Seawise Giant in 2010 marked the end of an era. It remains the longest and heaviest self-propelled ship ever built, the undisputed king by the metrics of length and deadweight. Yet, the quest for scale did not end with its demise. Instead, it fractured and evolved. The title of "world's largest ship" is no longer a singular crown but a collection of them, held by a new generation of titans that dominate their specific domains. To understand them is to understand how the very definition of "bigness" at sea has changed.

A New Measure of Might

The fundamental shift lies in the metric used to measure greatness. The Seawise Giant was the champion of Deadweight Tonnage (DWT), a simple measure of how much weight a ship can carry. For a tanker, whose sole purpose is to move a heavy liquid commodity, DWT was the ultimate benchmark of capacity and value.

However, in the 21st century, the primary metric for most classes of mega-ships has become Gross Tonnage (GT). Unlike DWT, GT is not a measure of weight but of a ship's total internal volume. This seemingly technical change reflects a profound evolution in the global economy. The world has moved from an economy where value was primarily derived from the mass of raw materials being transported (the industrial age of oil and ore) to one where value lies in services, complex logistics, and consumer experiences.

For a modern cruise ship, the crucial question is not "How much does it weigh?" but "How many restaurants, cabins, waterparks, and theaters can we fit inside?" GT answers this question. For a modern container ship, the key metric is TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Unit), another measure of volume, representing the number of standard containers it can carry.Even the Seawise Giant, the king of DWT at 564,763 tonnes, was outclassed in GT. Its 260,941 GT was smaller than that of the four Batillus-class supertankers (up to 275,276 GT) and dwarfed by the modern crane vessel Pioneering Spirit (403,342 GT).The ascendancy of GT and other volumetric measures is therefore more than a footnote in naval architecture; it is a direct reflection of what our globalized, consumer-driven economy values most. The new titans are not just bigger; they are bigger in a different way, designed to enclose vast, complex, and valuable spaces.

The Four Successors - A Modern Pantheon

Today, at least four distinct vessels can lay a legitimate claim to the title of "world's largest," each representing the pinnacle of a specialized domain. They are the new kings, and their diversity illustrates the modern face of maritime gigantism.

1. The Strongest: Pioneering Spirit

Claim to Fame: The largest ship in the world by Gross Tonnage.

Function: This is not a transport vessel but a colossal offshore construction machine. A unique twin-hulled crane vessel, its primary mission is the single-lift installation and removal of entire oil and gas platform topsides, some weighing up to 48,000 tonnes, and the laying of deep-sea pipelines.

Significance: With a staggering GT of 403,342, the Pioneering Spirit represents the apex of specialized, heavy-industrial engineering. Its immense volume is dedicated to housing the powerful lifting systems, machinery, and accommodations needed for complex, long-duration offshore projects. It is a floating factory and construction yard, a tool of such scale that it fundamentally changes how offshore infrastructure is built and decommissioned.

2. The Longest: Prelude FLNG

Claim to Fame: The longest vessel currently in operation, and the largest floating offshore facility ever built.

Function: The Prelude is not a ship in the traditional sense of transport; it is a Floating Liquefied Natural Gas (FLNG) facility. It is permanently moored over an offshore gas field, where it extracts, processes, liquefies, and stores natural gas at sea, before offloading it directly onto specialized LNG carriers.

Significance: At 488 meters in length, it surpasses the Seawise Giant by 30 meters. With a displacement of around 600,000 tonnes when fully laden, it is also one of the heaviest floating objects ever constructed. The

Prelude represents the ultimate integration of resource extraction and industrial processing into a single, mobile (though rarely moved) platform, eliminating the need for long and expensive pipelines to shore.

3. The Most Populous: Icon of the Seas

Claim to Fame: The world's largest cruise ship by Gross Tonnage.

Function: A "floating city" or destination resort, designed entirely around mass-market tourism and the consumer experience.

Significance: With a GT of 248,663 and 20 decks, the Icon of the Seas is an architectural marvel designed to house an astonishing array of amenities, including a 17,000-square-foot waterpark, seven swimming pools, an indoor aqua-theater, and more than 40 restaurants and bars. It can carry a maximum of 7,600 passengers and 2,350 crew, a total population of nearly 10,000 people. Its size is driven not by the need to carry cargo, but by the commercial imperative to pack in ever more novel experiences, attractions, and revenue-generating venues, embodying the philosophy that for many modern tourists, the ship itself

is the vacation.

4. The Busiest: MSC Irina

Claim to Fame: The world's largest container ship by cargo capacity.

Function: The quintessential workhorse of the 21st-century globalized economy. Its purpose is the ruthlessly efficient transportation of consumer goods.

Significance: The MSC Irina and its sister ships can carry a staggering 24,346 TEU (Twenty-foot Equivalent Units). These vessels are the backbone of the global supply chain, connecting manufacturing hubs in Asia with consumer markets in Europe and North America. Every aspect of their design, from the bulbous bow that reduces drag to the advanced air lubrication systems that coat the hull in microscopic bubbles to reduce friction, is optimized for one purpose: to lower the cost of moving a single container by fractions of a cent. They are the physical manifestation of our interconnected world of commerce.

Part IV: Conclusion - The Unending Quest for Scale

Legacies of Steel and Ambition

The story of the world's largest ships, from the singular reign of the Seawise Giant to the diverse dominion of today's titans, is a mirror reflecting the evolution of our modern world. The Seawise Giant was a monument to a simpler, if no less ambitious, time. It was the ultimate expression of 20th-century industrial might, a tool forged for a single purpose: to move the maximum possible volume of a single, vital commodity. Its greatness was measured in raw, brutal mass—its deadweight, its displacement, its sheer physical presence.

The kings that rule the seas today are creatures of a far greater complexity. Their "bigness" is measured not just in mass but in volume, in capacity for experience, in logistical sophistication, and in the intricate web of systems that control them. The Pioneering Spirit and Prelude FLNG are not transport vessels but mobile industrial plants, embodying the extreme specialization of the energy sector. The MSC Irina is the silent, ruthlessly efficient engine of a globalized consumer economy, its form dictated entirely by the logic of the supply chain. And the Icon of the Seas is a product of the experience economy, a floating theme park whose scale is driven by the endless demand for novelty and entertainment. The journey from the Seawise Giant to the Icon of the Seas is a journey from a tool of industry to a product of leisure.

Through this evolution, one constant remains: the deep-seated human drive to push the boundaries of engineering, to build bigger, to achieve what was once thought impossible. The anchor of the Seawise Giant, resting in a Hong Kong museum, is a testament to that enduring ambition.

Yet, the questions that today's naval architects and engineers must answer are profoundly more complex than those faced by the builders of hull 1016. The challenge is no longer simply, "Can we build it bigger?" It is now, "Can we build it bigger, smarter, more maneuverably, more efficiently, more profitably, and with a genuine conscience for the planet it sails upon?" The saga of the world's largest ships is far from over. It is a story that will continue to be written in steel and software, a grand narrative of our triumphs, our ambitions, and our most profound responsibilities.